Amador Fernández-Savater

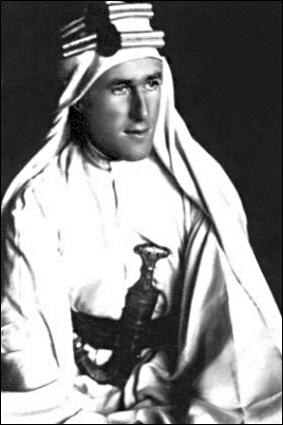

In 1929, the editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica commissioned T.E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia, to write the entry on “guerrilla warfare” for its 14th edition. In the ensuing text, Lawrence set out the theoretical foundations of the Arab guerrilla against Turkish rule that he himself had led between 1916 and 1918. At Acuarela Libros we published that wonderful text in 2004, along with a study by one of the members of the Italian writers’ collective Wu Ming – specifically, Wu Ming 4 (this autumn, by the way, we will publish Estrella de la mañana, a novel by Wu Ming 4 that features Lawrence as the main character). You can read Science of Guerrilla Warfare here.

In 1929, the editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica commissioned T.E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia, to write the entry on “guerrilla warfare” for its 14th edition. In the ensuing text, Lawrence set out the theoretical foundations of the Arab guerrilla against Turkish rule that he himself had led between 1916 and 1918. At Acuarela Libros we published that wonderful text in 2004, along with a study by one of the members of the Italian writers’ collective Wu Ming – specifically, Wu Ming 4 (this autumn, by the way, we will publish Estrella de la mañana, a novel by Wu Ming 4 that features Lawrence as the main character). You can read Science of Guerrilla Warfare here.As I was rereading the two texts (barely 60 pages in total) over the last few days, I kept getting flashbacks to images of our recent experiences in Madrid during the first week of August: the occupation of Plaza del Sol by the police (this central square in Madrid been taken over by spontaneous camps and an information point since the May 15 mobilisations), the mass demonstrations circulating around downtown Madrid in the middle of the usually sleepy summer, and the final liberation of the square on the night of the 5th – another of those true celebrations that the 15-M movement is getting us dangerously used to.

The reason one thing led me to the other is that there are powerful resonances between the two: our “victory” was Lawrence’s. I will quote some extracts from each of the texts, alternating them with my own reflections on the non-battle of Sol. What do I mean by “non-battle”? It is the key concept of Lawrence’s guerrilla: warfare from a distance, so that your adversary never gets the chance to fix on a target.

Above all else, victory depends on cognitive action, on an arbitrary change of perspective that does not defy the force of the enemy but defuses it, avoids it and renders it useless. (WM) If there is a strategically important geometric point on the map of the war theatre, victory does not necessarily entail conquering this point, in which the enemy feels invulnerable, but rather in modifying the entire map so as to turn it into a point of secondary importance. (WM)

Shift the action elsewhere, insist on other points, go elsewhere and leave the enemy entrenched in the defense of a place that has become useless. Mobility is worth more than strength. (WM)

The garrison of Medina, reduced to an inoffensive size, were sitting in trenches destroying their own power of movement by eating the transport they could no longer feed. We had taken away their power to harm us, and yet wanted to take away their town. What on earth did we want it for? They were harmless there. On all counts they were best where they were. Let them be! (L The Seven Pillars of Wisdom and Science of Guerrilla Warfare)

Sol was our Medina. On Tuesday August 2nd, all that remained of the camp and information point that had been the nerve centre during more than a month of mass demonstrations around Spain was evicted by the police without niceties. The police action was virtually presented as a clean-up: they pulled off our beautiful plaque, for example, and threw it into a rubbish container. And that’s how many of us felt: wiped off the map without the slightest explanation, as if we were nothing but trash, as if we had never existed. They wish!!

We decided to show them they were wrong. That same afternoon we self-organised a peaceful demonstration at Sol, which by then was already occupied by the police. There were many of us, more than anybody could have estimated in advance. The initial idea was to “reconquer” the square, but that was an impossible goal. The balance of forces was clearly not in our favour. For a long time we stayed there, making noise in front of the police cordons that had been set up at each of the nine arteries of the square. What to do….?

Suddenly, there is a shout: “ciao ciao ciao, we’re off to Callao” (another square in downtown Madrid). The slogan catches on. Bye, we’re off, you’re on your own. Instead of confronting them, we turn our backs. A half-turn, and voilà, the whole of Madrid is ours. We start moving: first Callao, but then onto other public spaces in the city: Gran Vía, Alcalá, Paseo del Prado, Atocha, a mass assembly at Plaza Mayor at midnight… Several thousand people, but not a single flag or acronym, mixture and diversity, pure anonymity. A change of perspective, a change of scenery, a change of interlocutors, a change of affects. We are no longer shouting our rage at impassive police, now we are present all over the city. We transform a situation of impotence into potency. The joy of dodging. Lawrence was right: enter Sol: what on earth for?

Never be in the same location as the enemy, force the enemy to bleed, make defence and self-maintenance increasingly expensive, to the point of moral and economic collapse. (WM)

We had nothing material to lose, so we were to defend nothing and to shoot nothing. Our cards were speed and time, not hitting power. (L)

The police Garrison at Sol remained in the trenches, protecting the void. One day, two days, three… We have all the time in the world. And what about them? All this comes at a cost, which increases with each passing day. What image of Madrid is being transmitted all over the world? What are the shops in the square supposed to do? How long can you keep the city centre (also the tourist and shopping centre) closed to pedestrians? The operation is not sustainable: the police officers have to do overtime, there are not enough reserve forces to cover 24 hour shifts, the exhaustion is increasingly obvious, the Police trade union (SUP) issues a press release strongly criticising the decision to occupy Sol. “They were forced to eat the animals that they could no longer feed…” The whole caboodle came crashing down four days later. On the Friday night we happily entered the liberated square and we left again a few hours later, without setting up the information point again. What on earth for? “Every guerrilla fighter is a communications hub.” It’s the best way of showing that it isn’t about the ownership of territory.

The Arabs were fighting for freedom, a pleasure only to be tasted by a man alive. (L)

Being irregular, the men were not units, but individuals, and an individual casualty is like a pebble dropped in water: each may only make a brief hole, but rings of sorrow widen out from them. The Arab army could not afford casualties. (L)

Lawrence used a strategy of removal. Instead of fighting the enemy, you abandon and disorient him. (WM)

It is not about avoiding conflict, but approaching it in different terms: less to do with surface than depth. Lawrence wondered: “How many posts would the Turks need to contain this attack in depth, sedition putting up her head in every unoccupied one of these 100,000 square miles?” And we can ask ourselves the same thing: “How many officers would the police need to contain an attack in depth, sedition raising its head in every square in Madrid?”

In reality, we are our own worst enemy. We are, when we think “Turk-style”. And we think Turk-style when we accept the definition of conflict as a direct confrontation between two symmetrical blocks. That’s where we lost in the past, we lose now, and we will continue lose. The political authorities were desperately wishing for the following scenario: us, armed with sticks and helmets, trying to cross the police cordons and take back Sol. A head-on clash. An abstract and totally self-referential dynamic. Dozens wounded and arrested. Dozens of rings of sorrow and resentment. The split of the movement into those who are “violent” and “against violence”. An internal spiral of accusations and denunciation. Gradual isolation and criminalisation. As Lawrence explains, the strong impose battles on the weak. The strategy of the weak is non-battle.

How would the Turks defend themselves? No doubt by a trench line across the bottom, if the Arabs were an army attacking with banners displayed. But suppose we were an influence, a thing invulnerable, intangible, without front or back, drifting about like gas… The Arabs might be a vapour, blowing where they listed. Our kingdoms lay in each man’s mind. (L Science of Guerrilla Warfare and Seven Pillars of Wisdom)

A thing invulnerable, intangible, without front or back… Without leadership, or headquarters, or a closed identity (anti-system, leftist…) Nothing that can be captured, taken apart, occupied, pinpointed. As Anonymous say in their press releases, the squares are us and we are everywhere.

We think Turk-style when we start to believe that the real achievement is the conquest of a territory. There were thousands of discussions about this during the debates on whether or not to strike camp and move out of Sol. Sol is not a homeland, it is a symbol. The symbol of a different way of doing things, a different narrative of the world and a different framework of the possible. Does a symbol need a physical presence? Certainly, but the physical presence of the symbol-Sol is not so much the tarpaulins and tents, but rather our behaviour, our forms, and our vision. Horizontality, respect, collective intelligence, inclusiveness, active non-violence… Sol is a state of mind, not a physical space. It is a fiction – endlessly reproducible (in other places) and redefinable (with other content) –, not an entity crystallised in a series of fixed characteristics.

Sol had been occupied, then the idea was to turn the whole city into Sol.

The guerrilla fighter’s strong point lies more in the ability to infect the civil population with his or her own ideas than in direct military efficacy. The conflict is not physical, but moral, political. (WM)

It would be enough for two per cent of the population to take up arms, if the other 98% practice passive resistance and what we could call psychological pressure on the enemy army. (WM)

The uprising must be able to count on a friendly population, not actively friendly, but sympathetic to the point of not betraying rebel movements to the enemy. (L)

There were undeniably a great many of us, especially given that it was August and many locals had left town. Nobody expected it, the estimates that led the authorities to evict Sol were certainly wrong. But even so, we were still a minority. Where does the strength of that minority lie? It is not about numbers, it is not about confrontational capacity… so? Why did the police allow our instinctive, spontaneous routes through the city?

Like in the actual camp at Sol, our strength lies in the living link with what Juan Gutiérrez calls “the still part of the movement” and Lawrence calls the “friendly population”. The people who do not get involved in the organisational activities of the 15-M movement, but feel that it concerns them, and support it however and whenever they can. This sympathy is no trivial matter. On the contrary, as Wu Ming says, it exerts a decisive psychological resistance on the enemy: what do I risk by suppressing the demonstrators? What currents of opinion will it provoke? How will that translate into votes in the elections? 15-M is not just those who are there, on the streets or at the assemblies, but an energy that flows inside and out. We will call the minority that keeps alive the ties with that still part of the movement the “majority minority”.

In an assembly that was discussing possible strategies for action in response to the police occupation of Sol, somebody said: “we mustn’t forget that our actions are not only our own.” I think this person was thinking about the still part of the movement: what types of languages and actions keep our links with it alive, and what types weaken these links. We will call the minority that has lost its ties with the still part of the movement the “ghetto”. Power is eager to take on a ghetto, it is crying out for confrontation. Ghettoes are weak, because they are isolated or may even have the population against them. Our actions are not only our own, we have to nurture a space that many other people can identify with and feel that they belong to. To see and to listen beyond one’s self, to preserve the power of anonymity.

To convert every subject to friendliness. (L)

It is interesting to reflect on the insults that are used against the 15-M movement: dogs, rats, vermin, lice, bedbugs… It is as though they were trying to dehumanise us by denying us the capacity to speak. These are not the insults you use against an adversary (where there is an obligation for mutual recognition), but against an enemy (which you hope to simply get rid off). Destroying the other means “unknowing” them first. To counteract the destructive power of these stereotypes, from the very first day the people involved in 15-M made a huge effort at humanisation, talking in first person, as an individual, simply another human being, seeking empathy, recognition (“we are like you”) and a sensitive approach to the other. Even with the police, at very tense moments. “We see people under the uniforms”, we chanted at Sol. People under uniforms, people under stereotypes, it’s the same thing. The common element is humanity.

The enemy is a contingency, not a reference for action (WM)

The presence or absence of the enemy is a secondary matter. (L)

Lawrence’s guerrilla is not an anti-Turkish guerrilla. It does not define itself in relation to the Turks, and it is not aimed against them. The freedom that it seeks is not a “freedom from”, but rather a “freedom of” or “freedom to”. It is not a guerrilla that sets up a clear border between itself and that which is “not guerrilla”, but rather tends to broaden its boundaries, to include all who are sympathetic, because each person is important and everyone can play a role. This means it is not isolated, and as such, it is not weak. The idea is more about the construction of springboards for thought and for life, than about simple rejection that never leaves the circle of that which is rejected. It is active, not reactive. Its reasoning is not based on ideological principles set down on some tables of the law. Instead, it specifically thinks about what increases its power, or in other words, its capacity for action. What alliances, what actions, what movements? It is expressed much more through the joy of being together than through a resentful desire for revenge. It doesn’t complain, and it doesn’t curse its luck. It doesn’t seek scapegoats, or cultivate an inner feeling of inferiority. It doesn’t endlessly repeat how terrible the Turks are (and how good the Arabs are in comparison). It doesn’t passively wait for answers to come to it from outside, or seek salvation through the punishment of the other. It accepts responsibility for itself and the way the world is going. It produces new realities, it does not only put up with and cry out against the existing one.

I’m talking about the Arab guerrilla according to Lawrence, but I am also thinking about the best of 15-M.

There are two key elements to the guerrilla-movement: mobility as the best weapon of defence; and thought as the best form of attack. To remove the targets from the enemy and “convert each subject to sympathy and friendliness” are the keys to victory. (WM)

We will have to keep this constantly in mind over the next few months if we do not want to let ourselves be pushed into the dead end streets of repression/reaction or the political chessboard of “the two Spains”.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario